In a nutshell: Today's typical navigation-grade motion sensors are about the size of a grapefruit, helping steer ships, planes, and vehicles in conjunction with GPS signals. This means they always need satellite connectivity to function, but a new breed of "quantum compass" could eventually let us ditch the satellites entirely.

The idea of using quantum technology for navigation isn't exactly novel. The technique relies on sensors called atom interferometers that can track position and motion without any need for GPS satellites. But the problem was that to get the required navigation precision, it had to be monstrously huge to hold six large atom interferometers – big enough to fill an entire room. However, this is changing.

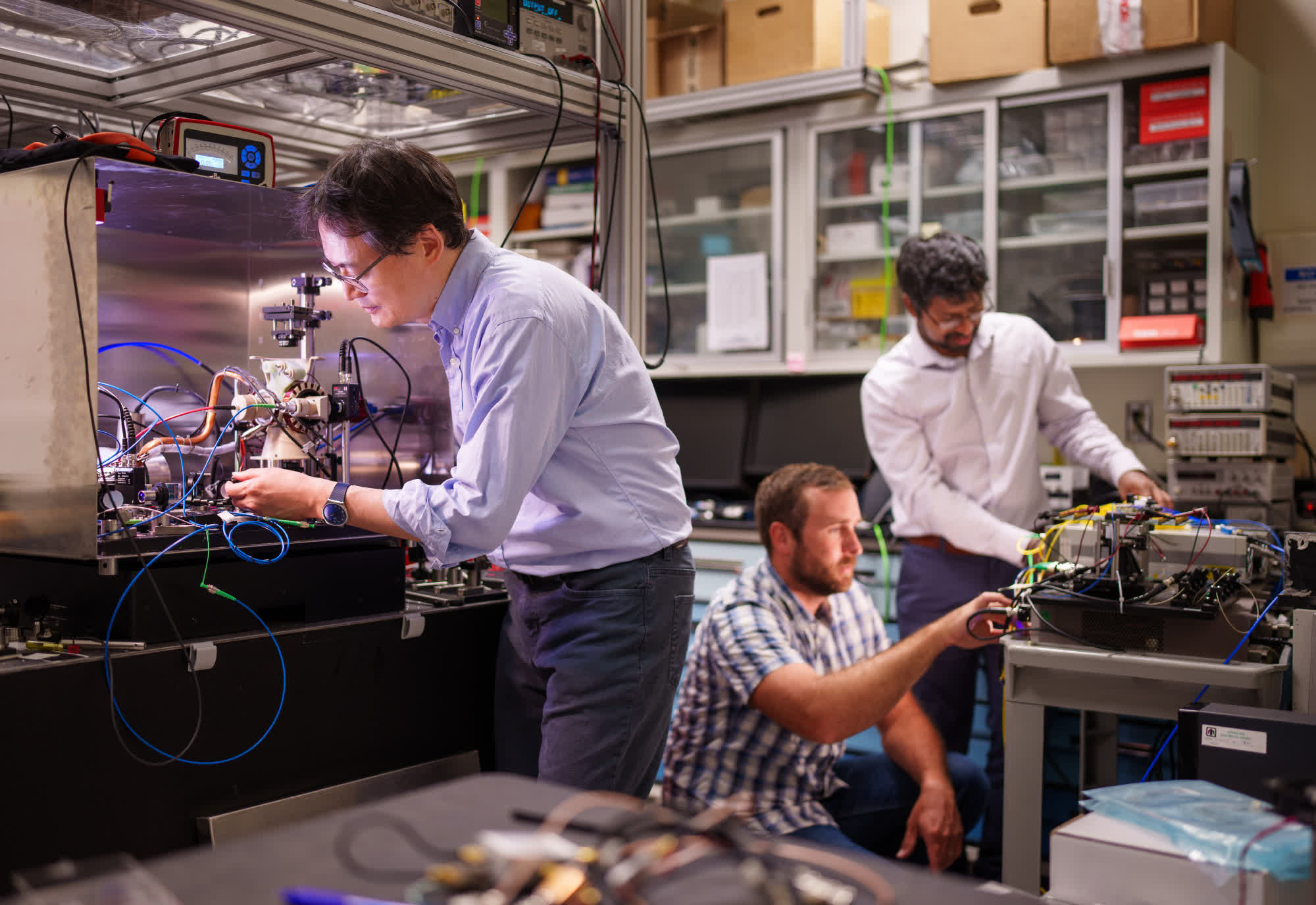

A team at Sandia National Labs has developed ultra-compact optical chips that can power those quantum navigation sensors in a package small enough to stick basically anywhere. It's all about replacing the bulky laser systems normally needed for the atom interferometers with tiny integrated photonic circuits.

The scientists say that reducing dependency on GPS is important because satellite signals can be disrupted or spoofed. This can cause major headaches for military operations or automated transport systems.

"By harnessing the principles of quantum mechanics, these advanced sensors provide unparalleled accuracy in measuring acceleration and angular velocity, enabling precise navigation even in GPS-denied areas," said Sandia scientist Jongmin Lee.

One key piece they developed to achieve all this is a modulator that can precisely control and combine multiple laser frequencies from one source, eliminating the need for stacking individual lasers.

In addition to being more compact, the chips are also more robust against vibrations and shocks. That ruggedness could allow deploying the quantum sensors in all kinds of challenging environments that would wreck today's models.

Then there's the cost factor. Those room-sized quantum navigation systems aren't just physically huge; they're hugely expensive, too: a single laser modulator can run over $10,000. But by using semiconductor manufacturing to produce their chips en masse, the Sandia team hopes they can drive costs way down to boost affordability.

"We can make hundreds of modulators on a single 8-inch wafer and even more on a 12-inch wafer," said Sandia scientist Ashok Kodigala.

These applications could also extend far beyond just navigation and GPS backups. The team is exploring using the quantum sensors to detect subtle gravitational changes for mapping underground resources and structures. The compact optical chips have promising potential in areas like LIDAR, quantum computing, and optical communications, too.

The findings were significant enough to be published as the cover story in the journal Science Advances.

Image credit: Craig Fritz