What just happened? Anthropic has become the latest artificial intelligence startup to be sued by authors, who claim on this occasion that it used pirated copies of their work to train its AI model, Claude. The three authors in the class-action lawsuit say Anthropic "built a multibillion-dollar business by stealing hundreds of thousands of copyrighted books."

Writers and journalists Andrea Bartz, Charles Graeber, and Kirk Wallace Johnson brought the lawsuit, which seeks class action status.

The suit alleges that Anthropic downloaded known pirated versions of the plaintiffs' work, made copies of them, and used these pirated copies to train its LLMs.

"Anthropic styles itself as a public benefit company, designed to improve humanity. For holders of copyrighted works, however, Anthropic already has wrought mass destruction," the complaint reads. "It is no exaggeration to say that Anthropic's model seeks to profit from strip-mining the human expression and ingenuity behind each one of those works."

The suit also argues that Claude's ability to generate text, particularly "cheap book content," has been made possible by training it on people's writing without their permission or compensation.

"For example, in May 2023, it was reported that a man named Tim Boucher had 'written' 97 books using Anthropic's Claude (as well as OpenAI's ChatGPT) in less than [a] year, and sold them at prices from $1.99 to $5.99. Each book took a mere 'six to eight hours' to 'write' from beginning to end," the complaint states.

"Claude could not generate this kind of long-form content if it were not trained on a large quantity of books, books for which Anthropic paid authors nothing."

Anthropic is alleged to have knowingly used The Pile and Books3 datasets for its training, which incorporate Bibliotik, an alleged "notorious pirated collection." The suit said this allowed Anthropic to avoid paying licensing costs.

AI companies being sued for stealing copyrighted work to train their LLMs has become a common sight. OpenAI and others have also been hit with lawsuits from authors, artists, publishers, music firms, and more.

OpenAI previously claimed it would be impossible to train AI models without using copyrighted content. The leader in the generative AI field has today signed a deal with Condé Nast, allowing ChatGPT to reference stories from The New Yorker, Bon Appetit, Vogue, Vanity Fair, and Wired.

Anthropic was sued by three music publishers last October for infringement of their copyrighted song lyrics. Earlier this week, the company asked a US federal court to dismiss much of the case to focus on whether training AI using copyrighted work falls under fair use, which is something many AI firms and executives have claimed.

I startups Udio and Suno, who are also being sued by music groups, have admitted to scraping copyrighted tracks, argue that doing so is fair use and that the music it generates doesn't feature samples straight from the original songs.

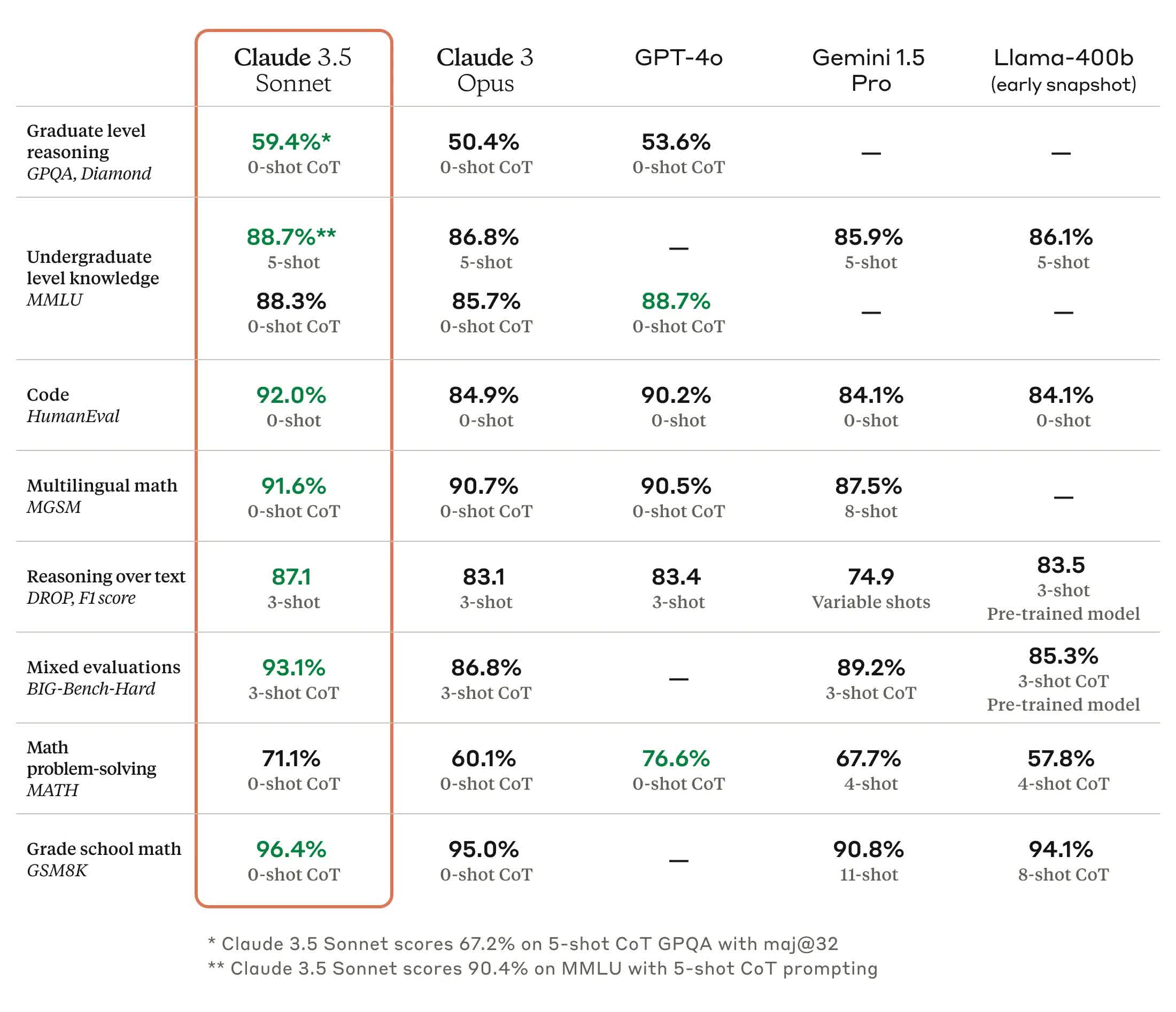

In June Anthropic launched its Claude 3.5 Sonnet AI model, claiming it beats GPT-4 Omni in several metrics. The company is founded by former members of OpenAI, and last year received a $4 billion investment from Amazon and $2 billion from Google.

Authors sue Anthropic for allegedly using pirated copyrighted work to train Claude

.svg/1200px-Great_Seal_of_the_United_States_(obverse).svg.png)