I am generally suspicious of games that people say are "better with friends," simply because most things are. Manual labor, paying taxes, repeatedly hitting your thumb with a hammer---these are all things that are "better with friends." Humans are social creatures, and company can make both miserable and pleasant things a whole lot better. "Better with friends" is rarely a good selling point.

I am generally suspicious of games that people say are "better with friends," simply because most things are. Manual labor, paying taxes, repeatedly hitting your thumb with a hammer---these are all things that are "better with friends." Humans are social creatures, and company can make both miserable and pleasant things a whole lot better. "Better with friends" is rarely a good selling point.

Wolfenstein: Youngblood isn't really just better with friends; it requires them. Sure, you can play it solo, the game notes, ceding control of your ever-present companion to the game's questionable artificial intelligence, but to do so is often frustrating. I'll just underline it here, in bold permanent marker: I highly recommended that you don't bother with Wolfenstein: Youngblood if you intend to play it solely by yourself. Play some of it solo, sure. I did! But all of it? Definitely not.

That's not a ding against Youngblood. The game has always been positioned as a cooperative experience meant for two players---the $40 deluxe release even comes with a buddy code for someone else to download the game for free, the only restriction being that they can play solely with whoever gave them the code. It's a co-op shooter. To criticize it for not being something other than that is unreasonable.

In Wolfenstein: Youngblood, you play as Zofia and Jessica Blazkowicz, the twin daughters of previous series protagonist B.J. Blazkowicz and his wife, Anya Oliwa. Set in a world where the Nazis won World War II and achieved world domination, the game begins in 1980, roughly 19 years after The New Colossus, which ends in a new American revolution against the Nazi occupation. By the start of Youngblood, that revolution has succeeded, and Jess and Soph have grown up together on the Blazkowicz family farm in Mesquite, Texas.

As the daughters of resistance fighters who liberated America from Nazi occupiers, they've been raised to be survivors. Even though they grew up in the relative safety of liberated America, the Nazis have continued their despotic reign abroad. Hating Nazis runs deep in Zofia and Jessica, and killing Nazis is in their blood. So when their father goes missing in occupied Paris, the brash 18-year-old twins seize the moment, stealing a helicopter and some power armor in order to find their father and join the family's Nazi-killing business.

And they are so freaking hyped to kill Nazis.

Youngblood is built from the ground-up for teamwork. Enemies are tougher to sneak up on or fight head-on, so you need to decide on an approach and communicate the best way to execute. Bosses and firefights are infuriatingly difficult without a real person to coordinate with---it's maddeningly unclear what you can expect when getting into a firefight, as enemy reinforcements stream in with no parseable logic, making for grueling shootouts when playing solo that are much easier to handle with someone watching your back. But even with a partner, things get harder than they have to be if you don't comb over the game's small-but-intricate maps, full of secrets and hints that might give you an edge in achieving your goals. Without taking the time to do that, you can have a tough time early on as you face super-soldiers high above your own level too early in the game to have a decent arsenal of skills or weapons.

MachineGames' Wolfenstein series is known for being fun-as-hell throwbacks to a tougher, denser era of first-person shooting. While you technically have the option of being stealthy or going in guns blazing, all roads eventually lead to the latter. How could they not? These guns are big and loud and full of purchasable upgrades. Few things are more Wolfenstein than a long corridor obscured by the fireworks of flashing muzzles and the red of Nazis reduced to raw meat. Few games depict the weighty, cathartic mess of digital shooting like Wolfenstein games do, and Youngblood easily earns the Wolfenstein name in this regard.

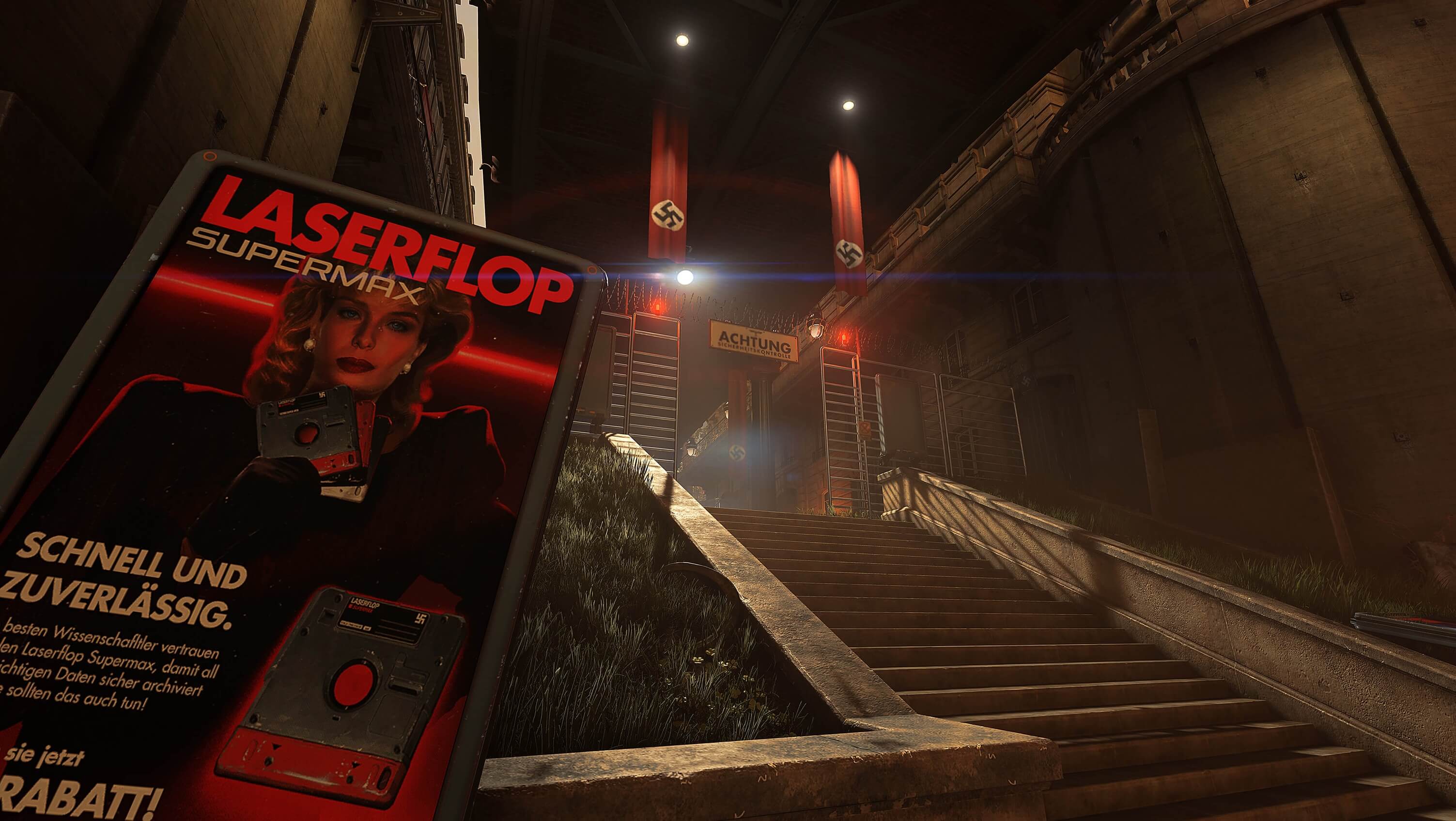

Youngblood's biggest departure is structural, which could be due to Dishonored developer Arkane Studios' contributions. After an opening mission set on a zeppelin, Youngblood deposits you in Nue-Paris, a web of three small, open-ended maps with lots of interiors to explore, linked by a fast-travel system. Each district has a tower that holds a vital part of the Nazis' Paris operation, and it's up to you to figure out how to break into each.

That is the immediate goal of Youngblood, one that you won't be able to accomplish until you've spent some time taking on side missions of your choosing. Some might give you leads for finding a route into one of the towers; some might just help you level up and upgrade your skills to take on the tough foes lurking in each tower. You could choose to not do these side missions and storm the towers immediately, but I wouldn't recommend it.

Most of the important technical aspects of playing Wolfenstein: Youngblood aren't unexplained, just easy to miss. Part of this is the easily ignorable method for teaching players how the game works. The tutorials are delivered by collectible laptops that are mostly in plain sight but not always placed in areas you have to be in. That means it's possible that you never learn how to use the special ability you start with (easy enough to figure out on your own) or that enemies have different armor types best handled with different guns (it will ruin your day if you never learn this).

That said, as a co-op game first and foremost, it is not built with solo convenience in mind. You cannot pause your game, even if you're playing offline. Safe spaces abound for you to hide out, and there's a hub area purely for chilling, but you play Youngblood at its pace, not yours. The meatiest and best bits of story are delivered via collectibles---an odd choice since stopping to read newspaper clippings isn't really something you can do often in a co-op game. But it makes sense once you see that Youngblood intends for you to return to all three of its districts often, completing side missions throughout the campaign or keeping Paris Nazi-free in the postgame with different partners. This is truly fun to do---tearing through Nazis in this game is a goddamn joy---but without the rich storytelling the series is known for, it's a little bit hollow.

A consistent theme of Machine Games' Wolfenstein saga is facism as a fickle, self-immolating ideology, incapable of sustained control. In creating an alternate history where Nazi Germany has conquered the world, the series argues that fascism yields no ideal dream to achieve---just a growing list of public enemies and increasingly deranged despots enabled by the complacent.

As a game about the next generation, Wolfenstein: Youngblood becomes a story about the future, and while its spare story is largely unconcerned with digging into any perspective beyond "f*ck Nazis," the primary division between the facists and everyone else is tomorrow. Youngblood, however briefly, contemplates the responsibility we have toward raising the next generation with the skills necessary to defend freedom---to fight for a future, any future, better than this one.

It's too brief a story to truly do any of these ideas justice, and that brevity makes provocative narrative turns less appealing---a resistance leader from the previous game is now the head of the FBI, but without further context, that rings false to The New Colossus' revolutionary spirit. Wolfenstein is one of the few video games where Nazi ideology is not something that sprang from some dark foreign ether, but rather a movement that took advantage of existing fear and bigotry. But since we're immediately sent into the middle of another Nazi conflict with the more pinpointed goal of saving a family member, we don't, unfortunately, get a look at what the revolution built over the previous 20 in-game years. Youngblood leaves Wolfenstein's dream mostly in suspended animation, accomplished, in part, but also unseen. It is, it seems, a job for another game, not this one.

It's tempting to want Wolfenstein: Youngblood to be the rousing third chapter in a terrific revival of a classic franchise, but it's not. Instead, it's a fun, off-kilter experiment, a good game about doing good with your friend. Because killing Nazis is good, but it's much better with friends.